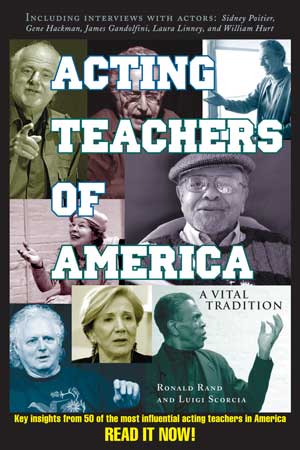

Acting Teachers Of America

Interview

Loyd Williamson with Ronald Rand

RR: Who have been most influential in how you teach students and direct actors?

LW: Sandy Meisner; that an actor’s behavior must ultimately come from his connection to another actor. As he put it, it must come from off the other fellow. For my own part, as I watched the scene work of my colleagues, I began to realize that there was a very clear physical component of this connection, that an actor’s behavior could come from off the other person only if their body was open and vulnerable to the impulses from the other actor. As my training with him grew, I realized that this openness was necessary to experience the setting of the play, the elements of your own character, and even being able to experience the specific meaning the moments of scene.

Harold Clurman: that a director need not follow anyone’s school of training or method. When a director understands the play, the scene, and the needs of the actors, the director may use any tools. Harold was a great talent. He was a consummate master of theater, indeed one of the most cultured human beings I ever met. His common sense approach to his directing amazed me.

Anna Sokolow: that art and artists are rare and deserve our profound respect. She enriched my ability to see and hear in the presence of art. From her I came to understand that painting, music, poetry is vital to an actor, to the expressiveness of an actor’s body in motion.

Michael Shurtleff: a clear understanding of the structure of any scene, and how to recognize its moments. Michael’s work has been invaluable to me as an actor’s coach. You must understand (and respect) both the individual actor and the demands that a particular scene places on that actor. In film, the shooting schedule of any scene seldom bears any relationship to dramatic structure of the script, yet the actor must prepare each scene within the dramatic context, and produce any scene at any time.

RR: How have you changed the way in which you work with actors?

LW: For me the operative word here grown rather than changed. The basic concept on which my technique rests has not changed. It came out of my instincts going back to childhood---we connect with our world through our senses; our bodies come alive with these sensual connections; instinctively behavior flows out of us. Our behavior enriches our connections. This made sense to me as a child and it still does. How I teach this basic concept seems to evolve according to my own growth as a person. For example, as I have matured, the depth to which I seem to be absorbing life into my own body seems to grow with each year. With this depth, my connections to people and my surroundings---as well as my expressions of those connections---are becoming more simple and clear. My teaching technique seems to be following. The actual exercises that I have written are becoming more simple, direct and clear. One result of this deepen connection is that, above all, I have grown in respect and love for the actors with whom I the privilege of coaching and teaching.

RR: Why should an actor study the craft of acting?

LW: Because it is an art.

First, acting engages the most challenging moments in our lives. An actor must create the reality of those moments, and, most importantly, must live in those moments. The result---as in all art---is that the artist carries the audience though experiences pivotal in each of their lives. Conversely, in each day, people---certainly actors---deal with or ignore hundreds of details---many necessary---that are come from happenstance and clutter. Daily life seldom gives the actor time or space to fully experience the major moments of human existence. The everyday is hardly the model for the heighten world of the art. An actor’s craft is actually the actor’s path into the depths of truth of human existence. Training is the arena in which the actor learns to live truthfully in the pivotal moments of life.

Second, the parallel journey of an actor’s craft is that of developing a physical instrument---a body---that can process the most challenging moments of life. The actor’s body must be sensually alive to every part of the world around him and to the meanings contained in every part of that world. The actor’s body must be developed so that it is completely vulnerable and responsive to the circumstances that define that world. Only then does the body become a conduit though which an actor’s behavior can flow, instinctively and unmonitored. An actor’s mastery of physical technique allows this organic behavior to flow out of the actor’s body in a form that is completely true to world in which the actor is living. Physical technique includes a mastery of the body’s alignment, its muscular freedom, a totally responsiveness of breath, open sound, complete freedom in vocal range, a delicious feel for phonetics, and most especially, a limitless reservoir of expressive gesture.

Conversely, to the world of the art is that of our local coffee shop. Here the mundane, the commonplace behavior is not only appropriate, but charmingly acceptable, indeed even necessary. Here we often find ourselves holding certain forms of muscular tensions, havening skeletal misalignments, using casual or half realized energy, mumbling or blurring consonants and vowels into each other, sliding around in the highs and lows of the vocal range, and the using sloppy, unsupported sound. These are mannerisms, a rather endearing trait of most of us. They are often our way of bonding with our friends, our hometown buddies, and our parents, bothers and sisters, and the other folks that have known us since birth. For an actor to use the tools of his art in the loosely defined and casual setting of everyday society is not only unnecessary but can even be intrusive to good fellowship.

As Sandy Meisner thundered in class, “Life? Don’t talk to me about life! My life is a mess! What I know is acting!” An actor’s craft is the bridge that carries him from the sometime charming world of the coffee shop and into the vibrant, often profound world of the actor, the artist.

RR: How did you decide on the process you teach?

Ron, short form:

Actually I did not decide on a process; I watched it evolve. I have always been able to see the workings of the human body: its blocks, where in the body those blocks occur, and how to release them. My technique is simply a product of instinct. I can see the behavior in a performer before it occurs, or hear the sound they will produce before that speak or sing. I understood this forty years ago when I directed high school plays. Even then I was formulating training for actors bodies, a method that would enable actors to process what they are experiencing into clear, true, behavior. My work in the professional theater began during my own training in New York. It started an empathetic connection to my fellow actors in class and what they were experiencing in their bodies when they were acting. This expanded into observing their physical needs in rehearsals and performances. I also found that the work was equally valid with singers and dancers. In fact, I recently had a wonderful coaching session with an accomplished French Horn player. His length of sound expanded some four or more measures. The resonance of his sound grew to a whole new level of beauty.

RR: How necessary is talent for an actor to become a creative actor.

LW. To me, an actor is an artist. “Creative Artist” ? The terms are redundant. Specific to an actor is an intrinsic ability and compulsion for two things: First, living in an imaginary world of their own creation, and second expressing that life in vivid behavior. These are the two abilities are the ingredients that make up talent. They are obvious even in the awkward audition of an untrained actor. Therefore, in my opinion, talent is the given. It cannot be learned. Edgar Lee Masters in his Spoon River Anthology has old Fiddler Jones say, “The earth keeps some vibration going there in your soul and that is you. And if the people find that you can fiddle, why they fiddle you must for all your life.“ At the conclusion of the poem Fiddler Jones says, “I died with a broken laugh and a broken fiddle, a thousand memories and not a single regret.” That vibration in one’s soul is Talent: imagination and expression. In old Fiddler Jones his expression is in this fiddle; the actor’s instrument is his body. Beware. For the person to whom these gifts are intrinsic, whether they choose or not, their life’s devotion will be how best to give form, shape, and clarity to the talent that came for free.

RR, How should an actor begin to work on a role?

LW: Sandy Meisner once told me that at his particular point in his life, the only actress he’d go to watch on stage was Maureen Stapleton, because he never saw the work she had done on the role. In my opinion, an actor should begin creating a role giving over to the experiences that comes with sensory connection to the people the place, the era (clothes, setting, time, etiquette) with the people that surround him. In other words these experiences are the actor’s character being brought to life by the actor’s unique relationships in the world of the play or film. If the actor understands his craft, the script will guide the actor into a point of view out of which he or she becomes more clear about the meanings of his experiences. Gradually, the actor’s experiences of the other people, of the place and time, will open his motivations for entering the scene and motivations over the ark of the play. Out of these elements the character’s physical life will evolve. Conversely, I do not think that an actor should work on a part and then impose it into the acting experience. The development of a part should be organic, growing from connection to and experience of the world of the play.

To summarize this process from the viewpoint of the physical technique:

• Though the actor’s five senses he or she connects with his world.

• Experience occurs as the actor absorbs these sensory connections into the inner life of the body.

• From the activated inner life---experience---behavior flows out of the body that is always instinctive (organic), clear, and true.

Ron, cut or edit as you wish

Let’s go to an example. In a particular film script, the actor is playing newspaperman. He is interviewing a star baseball player. His immediate reason for being in the scene is to get some responses from a star baseball. As the actor gives over the connection between them, he begins his journey of experience. In the dialogue, he finds himself begging the ballplayer for responses. As the actor begins to beg, the experience the character has of himself is that he is afraid he will fail, and that he feels inferior in the relationship with the ball player. Because he feels no confidence is himself, he is trailing after the ball player, sort of hunching down looking up into the ball players face. This guy could never behave as if he were on an equal level with the star. These experiences lead the character into a halting broken speech pattern. Each discovery originates in the actor’s connection to the other actor and from the experiences that come out of the connection. From these experiences flows the character’s behavior. This leaves the actor with a character that is totally connected to the world of the play. The above example is a film, The Natural, the ball player is Robert Redford and the newpaper guy is Robert Duval. With Duval I have never seen a hint that he has worked on a character. Duval’s characters seem to be born living in the play.

RR: Do you place an emphasis on the actor understanding the playwright, his or her reasons for writing the play, and the world of the play?

LW: Absolutely. Understanding the playwright, the reasons for writing the play, and the world of the play is imperative, because we must have a complete understanding of a piece of art before we can interpret it. How is it possible for any artist to begin creating their work in a play with out knowing the basis out of which the playwright created the play? Distort the playwright’s truth and the world out of which it grows, and you will spend the entire production process trying to compensate for what is not organically present at the work’s inception. For example, let’s look at just two of the hundreds of elements in Shakespeare’s work. you can transport one of his plays out of its period, but only if you understand the Elizabethan world’s degree of rank, and have a feeling for overwhelmingly beautiful use of language. The new setting and era must support these elements.

RR: How much of a role does imagination play in the actor’s work on a role?

LW: It is the birthplace of every aspect of the actor’s creation and of every other aspect of the production. Unless an actor can create the imaginary world of the play or film, the actor has no world with which to connect. The actor, therefore, has no world to experience, nothing that will bring his body to life. Indeed, all aspects of the craft of acting will remain in the actor’s head, never coming to life in the actor’s body. With out connection there can be no experience. With out experience there will be no organic source to give rise to behavior.

For me, the following coaching session is an exceptional example of how imagination creates the actor’s world and how character and physical life itself comes from the actor’s connection to the world that he creates.

I am going to describe a particular set of coaching sessions. The actress involved is an extremely private person. She described this working process in a national interview, but wanted no names attached to it. I am using the following material only because I think that it can be most helpful to other actors, and because it is an outstanding example of the material discussed in this interview. The actress is Jody Foster, who remains one of the most talented people I have ever coached. First, her emotional range seems to be unlimited. Second, her body is completely free from defensive tensions. She has a natural vulnerability, when she is acting, that makes her almost transparent: whatever she is experiencing in any given moment is instantly available to whom ever is experiencing her performance. Finally, she is fearless.

Her grasp of this technique happened in three sessions. Her use of it was brilliant. She went straight from the coaching sessions to her work on set. The film is Nell.

When she arrived at my apartment, she first said, “I want to do something with this, referring to the way she moved. How does this person walk?” And so our work began. My first question was, “What is most important for you in creating a role?” If I remember correctly she said that it was struggles, the challenges that the character must face. Certainly her Oscar winning performance in Silence of the Lambs was a beautiful example of this. I asked, “Then when Nell’s her mother dies and her body is lying in their cabin, why does Nell put daises on her mother’s eyes?” We looked at several possibilities, I can’t remember what they were, but we finally settled on the simple fact that they were flowers (instead of silver dollars or the equivalent), and “why are they in the cabin, and where did they come from?” They were in the cabin because they obviously had special meaning for Nell, and perhaps her mother as well. Where did they come from? “ The forest.” From there we went to the script: Nell’s entire existence has been spent alone in the forest at night. She has never lived in the chaotic world that emerges with the sunshine. She also has never seen any person other than her mother, and in her early life her twin sister. What did she do in the forest? What was her life the woods? Well, in the very first moment of the script, we learn that flowers (daises that grow wild in the woods) are flowers in the forest are very special to her. She has only the life with which she has contact is that of the forest: its plants, animals, trees, birds, moss and grass, plus her beautiful fantasy life when she is dancing with her identical twin sister. Her life is her sensory connection to her world. By contrast, her life is not defined by ambition to achieve goals or by struggling with all the demands of the outside world. Her world is one of constant discovery. She is a person of total openness to her world. Her vulnerability is complete. Later in the courtroom scene where the state is challenging her ability to survive on her own in her forest, she summarizes her life for the court in a moving speech, the climax of which is, “my world is very simple”. That is why she is completely in awe when first sees a man’s naked body as he quietly, and respectfully enters the water when she is swimming one night, and why she is mesmerized by every detail that she sees when she is first driven into town in daylight. What is the role that imagination played in creating this part? She created entire life in forest though her imagination. The core of the entire film was Nell’s sensory connection to and experiences of this world. Later, even when she is defending her own life, she is defending her life of vulnerability.

Now to return to the beginning, how does this character walk? We began by exploring the world that surrounded Nell as she traveled through her forest at night. The actress began to create the forest, bits animals, trees, night sounds of birds, animals, creeks, wind in the trees, colors of wild flowers, moss. Jody began by stepping out of the apartment door and onto the metal stairs that dropped into my garden that surrounded the apartment. With her vivid creation of this night world, she seemed to be stepping into her forest. Her behavior became that of a child living in wonder of the world around her. Jody’s character of Nell was becoming the essence of vulnerability---the behavior that became the through line of Nell’s character in the film. She began to move down the steps with a light grace and freedom. Sometimes she would become excited with what she was seeing and she would run or perhaps laugh. (I don’t remember all of the details, nor do I wish to). Leaving the garden she bounded up the stairs like a young dear.

So how does a character walk? For me the question is, “how does a character live?” From the point of view of my physical technique for actors, all physical life---breath, gesture, sound, posture, all impulse for motion or sound---is a result. If is born in the actor’s sensory connection to his world, and his allowing sensory connection to flow into the inner life of his body. I use the word experience to describe a process: the inner life of the actor. This word I use to describe this activating of the inner life the actor’s experience. The world to which the actor connects is created through the actor’s imagination. The wonderful talents of the set designer, costumer, or property master are a marvelous help to the actor’s imagination. But unless endowed with meaning by the actor’s imagination they can never come to life.

RR: How important and valuable is your unique presence to the work that is actually occurring in the classroom?

LW: It’s essential. No matter the validity of the material, an actor can absorb the content of what is being taught only to the extent that the teacher can experience (lived in the material). This is true down to teaching period dance or memorizing choreography. Conversely, the teacher who has a superficial involvement in the content of the class, and, I might add a superficial connection with the actors in the class, will produce a class that is superficial (and to my mind, a waste of time). The teacher’s must be able to inspire actors to expand their involve in art beyond acting. For me, any one who has the privilege of working with actors must be constantly immersed in the world of art and the artists. The effective teacher leads their actors into a love of all art: of all eras, nationalities, and styles. The teachers are always developing their education in music, painting and sculpture, in literature including the novel, short story, biography, plays, essays, poetry. They must immerse themselves in history---of civilizations and cultures, an especially history of our theatre and its artists. The importance of the teacher in the classroom? The teacher is the leader, the source of inspiration for the actor. Through the teacher the student discovers new worlds. Thought the teacher the actor grows.

RR: You’ve devoted your life to the theatre: directing, teaching, producing. Do you believe it’s contributed to the theatre’s health, its continuity, and its value to our culture?

LW: That is a lovely question. Someone other than me best assesses my contribution. I wouldn’t presume.

As to continuity, I feel that each of us in the theater is a part of a continuum. Apprenticeship is still the heart of our life in the theater. We inherit our place in this art form from our mentors. I discussed the specific gifts to me of each of my mentors in our opening question. Each year reveals more clearly for me the origins of me work, what my what my own instincts brought to my work. The shaping, the molding of those instincts into the art of theater were the product of the artists under whom I studied. Further, I am still searching and discovering aspects of my work that evolved from my teachers. If I do not continue to understand what I inherited, then I cannot understand the journey I am traveling. Our next part in this process is our obligation to add our own contributions to what we have been given. This is our lifetime of developing our technique ofr conveying what we have discovered. Then comes the final mandate: we must pass on to others the discoveries that have come to us in this journey. The entire process is the highest from of professional health. Our work is not about us, but rather how we serve traditions that are far more important than each individual.

Tuesday, June 7, 2005

Interview

Kristin Davis with Ronald Rand

on Loyd Williamson

Kristin Davis

Kristin Davis appeared as Brooke Armstrong on the Fox television series Melrose Place and starred on HBO’s Sex and the City as Charlotte York, opposite Sarah Jessica Parker, Cynthia Nixon and Kim Cattrall. Ms.Davis and the cast received a Screen Actors Guild Award for outstanding performance by an ensemble in a comedy series in 2002. Her other television work includes the films Atomic Train, Deadly Vision, Murder in Mind, Three Days, and The Ultimate Lie. She has guest starred on Seinfeld, Friends, E.R., The Larry Sanders Show, and the adaptation of The Heidi Chronicles.

RR: What drew you to study with Loyd Williamson and how long did you study with him?

KD: I studied with Loyd when I was enrolled in the acting program at Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University. They had a very well rounded program and we had Loyd for three years. It was an important part of our training, partly because it was so rigorous physically. Since we were so young (nineteen to twenty-one), it really helped us to understand how hard we needed to work to be trained for the stage. As we progressed, we learned Elizabethan dance and worked with period costumes in our classes. It was so much fun, but also good preparation for the discipline needed to succeed in our profession.

RR: What were you hoping to discover about yourself and the craft?

KD: I knew intuitively how important your body is when you are acting, and I hoped that Loyd would help me learn to carry myself in a more open and powerful way. He focused on unlocking physical patterns that blocked full emotional expression. And though it was difficult, and I remember crying tears of frustration, he succeeded in ridding me of my teenage slouching. He also encouraged me, and all of the women in our class, to prize strength and grace in movement. Which meant a lot to me as a young woman.

RR: When you left the class, how would you describe what you learned as an actor?

KD: What I learned from Loyd took a while to sink in. He incorporated so many different techniques, I would find myself thinking, “Oh, I understand what he meant.” Years later, it still happens when I’m on set sometimes. I remember that I need to pay attention to my breath and open up physically to really be present in my performance. I think that, as all good teachers have, Loyd had a vision of me that I didn’t have when I began studying with him. It actually took me many years to grow into that vision. And that is really his biggest gift to me, to have pointed me toward the future of who I wanted to become as an actor.

RR: How have you been able to apply what you learned in your work?

KD: I’m happy to say that people often ask me if I used to dance and compliment me on my posture. This is all from my training with Loyd. And in terms of day-to-day work, I use specific techniques I learned from Loyd on a daily basis. The central idea that he gave me is that you can’t separate your performance from your body- they work together when you’ve taken care of yourself. And when you haven’t, your body can work against what you want to express in a scene.

Follow Me On: